The Origin of Meaning, Part 2: The Misattribution of Desires and the False Identity

The differentiation between the self and the rest of the world (the non-self) is the basis on which we construct our reality. From birth we sense and perceive differences between internal and external forces, and by 18–24 months of age, we also start to mentally represent the differences (Bertenthal & Rose, 1995; Gibson, 1995; Povinelli, 1995; Rochat, 1995).1

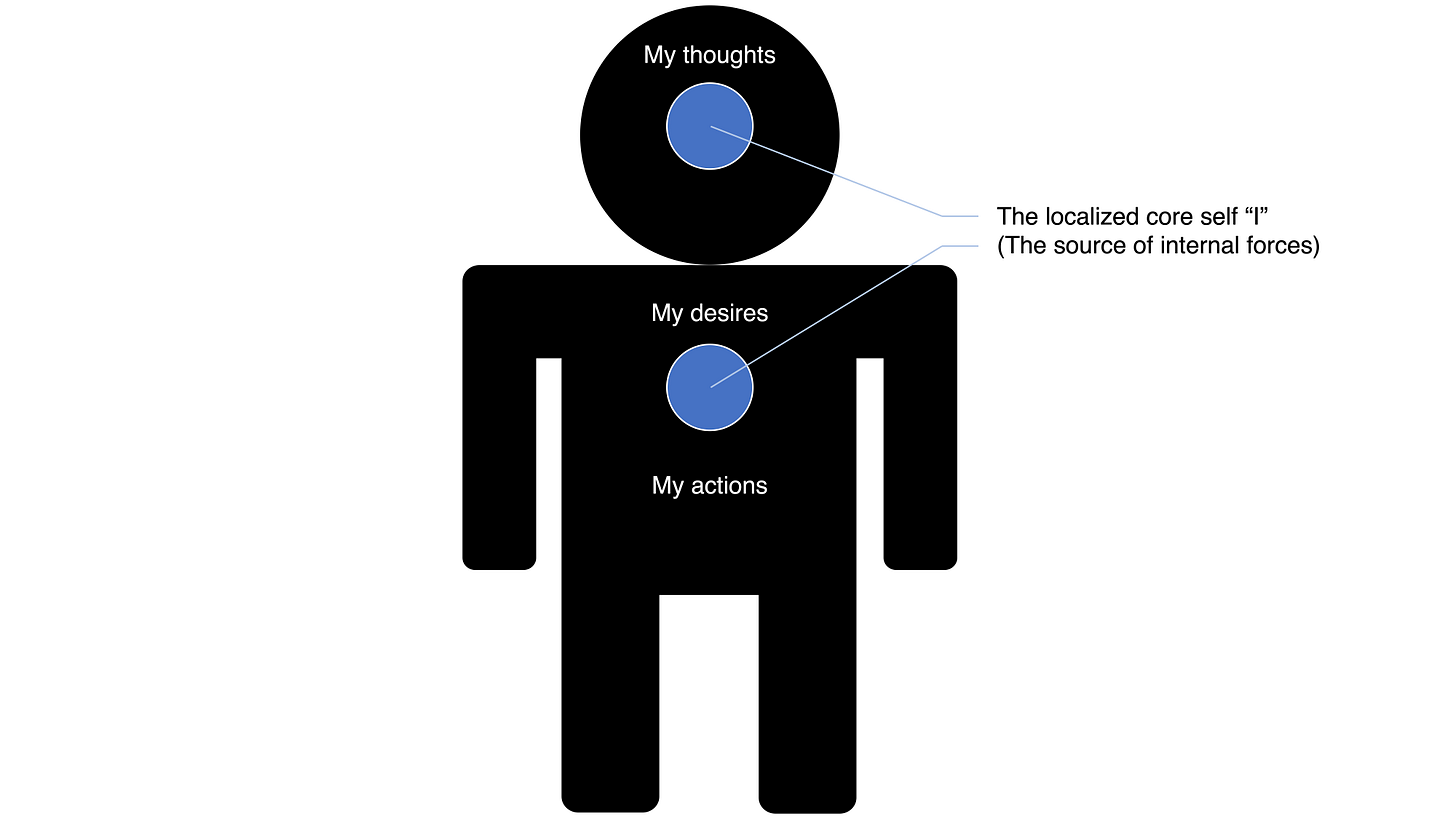

When mental representations of forces (i.e., psyches) and bodies are formed, self-other differentiation becomes clear-cut: We consciously identify ourselves as psychologically and physically separate entities in the world. The concept of the localized core self (i.e., the ego; with the corresponding symbol “I”) emerges, that is, the idea of the body as the source of perceived internal forces (Piaget, 1930/1972, Chapter V, Section 3; Watts, 1957; see Figure 1).2 As we view needs and desires we experience as originating from our bodies and perceive forces that differ from those needs and desires as originating from other bodies, we develop a conception of reality as a collection of separate and independent desires or wills.3

Figure 1

Images, Symbols, and Concepts of the Localized Self

Note. Self-concept consists of the core self (the source of self-characteristics) and self-characteristics. Self-concept develops as different characteristics are attributed to the core self (e.g., my actions, my desires, my thoughts) and the core self becomes correspondingly more complex (e.g., the doer of my actions, the desirer of my desires, the thinker of my thoughts). Throughout much of psychological development, attention is on developing self-characteristics, and therefore the core self is unexamined. The core self is placed in the head and chest because people commonly locate it in these regions of the body.

It is extremely lonely, scary, and confusing to think of ourselves as separate and independent bodies of needs and desires. It implies that the “outside” world has nothing to do with our needs and desires, and vice versa. Our needs and desires exist by and for themselves, and therefore the purpose of our existence is nothing but to fill the mysterious and absurd lack or void within. And other bodies exist for the same reason as we do. Each body is minding its own business to fill a lack and has no concern for others unless they are useful for filling the lack (not to mention the complete insensitivity and indifference of “inanimate bodies”).4

So we feel we have been thrown into an uncaring and alien world, which we somehow need to rely on to fill a lack. To make matters worse, as our knowledge of the world expands, we feel more and more alienated and vulnerable. With the view of a localized and isolated existence, becoming more intelligent and knowledgeable feels like a curse rather than a blessing.

The Restless and Endless Pursuit of Absolute Security and Lasting Fulfillment

We can suppress the terrifying worldview—the view that we live in an uncaring and alien world—as long as we keep our needs and desires satisfied. This is why we are constantly trying to control and make the world care about us and ensure satisfaction.

Although we make our meaning more and more reasonable to achieve more secure and lasting fulfillment (Loevinger, 1976), and even though we do make progress, our meaning-pursuit remains relentless due to the unchanged view of an alienated existence and identity. We tend to be ruthless and destructive in our endeavors because we see obstacles to our fulfillment as being posed by alien enemies or forces (Watts, 1973). Utopian visions are often followed by atrocities and devastation for this reason. Broader perspectives can come up with more holistic goals and plans, but if such goals and plans are implemented without awareness of our common source and identity, they will bring bigger disaster.

As long as we view ourselves as separate and independent bodies of needs and desires, it is impossible to genuinely do good for the world, no matter how fair and reasonable our ideals may be.5 Beneath our laudable ideals lies a huge void, and we are “helping” the world to fill it (so we care more about being seen as a peace-maker than about making the world peaceful, for example). This is why hypocrisy is commonplace. Recently, we have seen many people come to solve cultural divides, only to exacerbate them. Our extremely lopsided progress over the past decades is also a clear reflection of our alienated identity: We have made substantial progress in connecting us technologically, but hardly in our sense of unity and love.

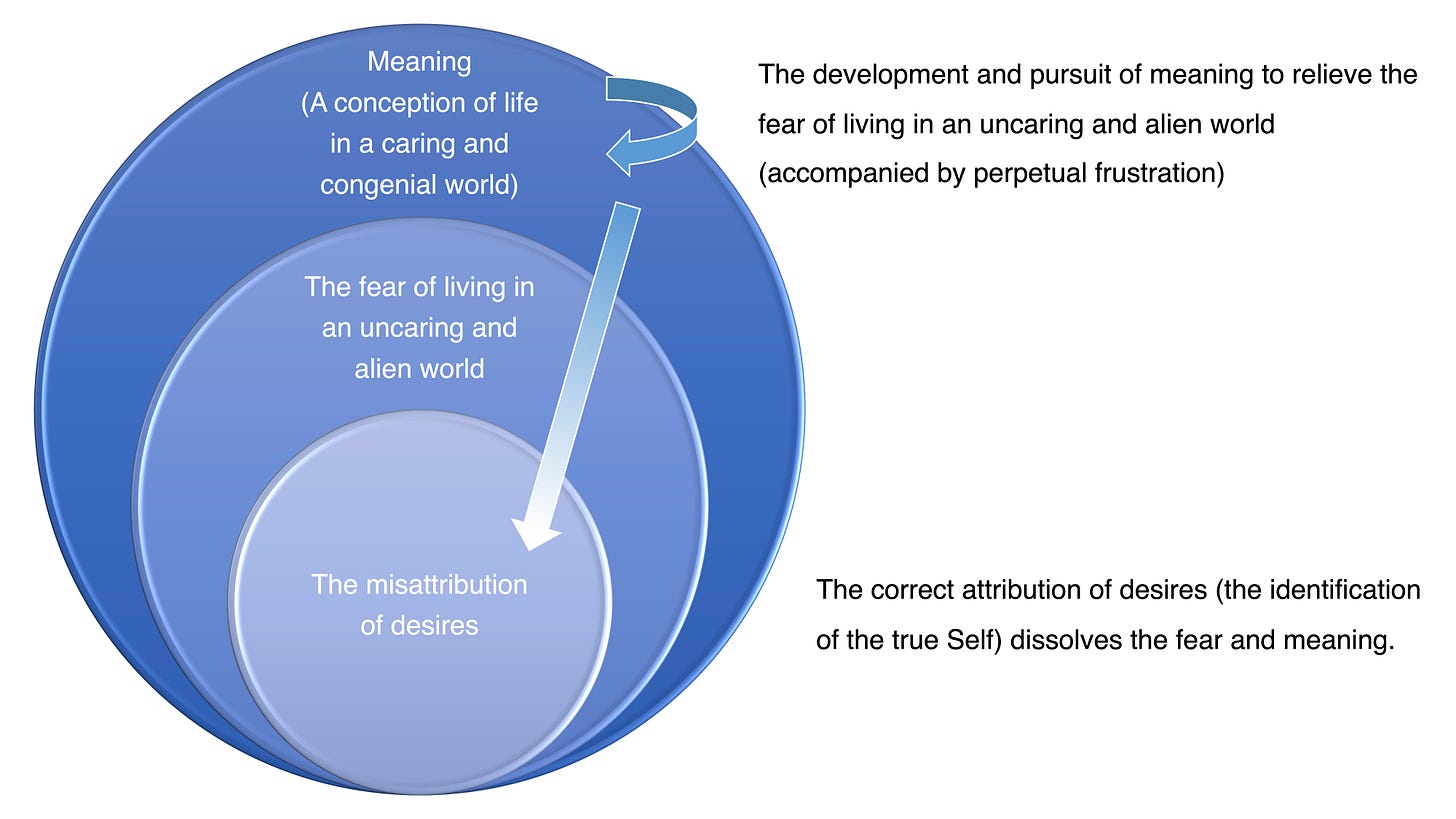

The conception of an alienated existence not only shapes our perception of the world but actively creates an uncaring and alienating world. The egoic pursuit of absolute security and lasting fulfillment, by its very nature, disconnects us from the world and brings conflict, insecurity, and unhappiness. In other words, the pursuit of meaning is self-defeating and self-perpetuating. Its progress merely suppresses the fear of living in an uncaring and alien world, partially and temporarily. To dissolve the fear, we need to get to the root of the conception of an alienated existence and correct the misattribution of desires (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Meaning, the Fear of Living in an Uncaring and Alien World, and the Misattribution of Desires

Note. Meaning is a person’s ideal worldview: life in a caring and congenial world, in which their most important needs and desires are securely and lastingly fulfilled (i.e., the opposite of their actual worldview: life in an uncaring and alien world).

The Identification of the True Self and the Transcendence of Meaning

After going through cycles of perpetual frustration, you begin to inquire into the driving force behind your pursuit of meaning: the origin and nature of your desires. You discover that desires you experience do not originate from your body but arise because of all the desires and forces you see as belonging to other bodies, and vice versa (i.e., codependent origination). You then further realize that since the desires of the self always arise inseparably from those of others, there is one desire ever arising: All desires of the world are one desire of the Self.6

You mistakenly thought that the desires of the world came from different sources because your attention was drawn to desires in action and their outcomes, which can conflict with each other and thus give the appearance of division and separation. Meanwhile, you were blind to the background and origin of your desires, which reveal one source and ground of all desires and forces of the world (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

The Fundamental Human Blind Spot: One Source and Ground of the Desires and Forces of the World

Note. The dashed blue circle indicates the fundamental human blind spot: one source and ground of the desires and forces of the world (symbolized by the yin-yang). Since attention is usually directed toward the outcomes of desires, the background and origin of desires is rarely examined.

Once you realize that you are not the self but the Self, which includes but transcends the former, preoccupation with needs and desires you experience starts to diminish, and the striving for self-fulfillment to subside (Wilber, 2000a).7 Although the expansion of your identity does not make you indifferent to fulfillment or happiness, you cease to seek it in desperation and with grim determination. The expansion has dissolved fearful and restless energy and brought peace and equanimity, which leads to harmonious action naturally and spontaneously. You no longer fight for unity, peace, and harmony. You have become unity, peace, and harmony. Your peaceful presence transforms the world and brings happiness and fulfillment as much as your harmonious action (Hanh, 2017).

You now understand that the world currently does not manifest enough love and care not because it is inherently unloving and uncaring but because it is largely asleep and unaware of its true nature and identity. So although you still see differences in the world, you see them purely in terms of self-awareness, without implying differences in identity or essence. Accordingly, you no longer try to defeat or eradicate unawakened aspects of the world but invite them to wake up.

Your meaning of life has disappeared. You no longer strive for an ideal future in which absolute security and lasting fulfillment are attained and life can finally become meaningful.8 You have stopped trying to escape from life and live fully as life. When life is the meaning of life, life is meaningless in this sense, and paradoxically, life is meaningful.

The pursuit of meaning originates from dissatisfaction with and alienation from life. Although the pursuit itself does not solve the dissatisfaction and alienation, the experience of the pursuit is what allows us to find better ways to relate to life and eventually go beyond it to fully embrace life. The frustration has been guiding us all along to awaken to our true Self and live in true happiness.

References

Bertenthal, B. I., & Rose, J. L. (1995). Two modes of perceiving the self. In P. Rochat (Ed.), The self in infancy: Theory and research (pp. 303–324). Elsevier Science

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (1999). Postautonomous ego development: A study of its nature and measurement. Integral Publishers.

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2013). Nine levels of increasing embrace in ego development: A full-spectrum theory of vertical growth and meaning making. https://www.cook-greuter.com

Gibson, E. J. (1995). Are we automata? In P. Rochat (Ed.), The self in infancy: Theory and research (pp. 3–15). Elsevier Science.

Hanh, T. N. (2017). The art of living: Peace and freedom in the here and now. HarperCollins.

Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego development: Conceptions and theories. Jossey-Bass.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper & Row.

Piaget, J. (1971). The child’s conception of the world (J. Tomlinson & A. Tomlinson, Trans.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1929)

Piaget, J. (1972). The child’s conception of physical causality (M. Gabain, Trans.). Littlefield, Adams & Co. (Original work published 1930)

Povinelli, D. J. (1995). The unduplicated self. In P. Rochat (Ed.), The self in infancy: Theory and research (pp. 161–192). Elsevier Science.

Rochat, P. (1995). Early objectification of the self. In P. Rochat (Ed.), The self in infancy: Theory and research (pp. 53–71). Elsevier Science.

Watts, A. W. (1973). The book: On the taboo against knowing who you are. Sphere Books.

Wilber, K. (2000a). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2000b). Sex, ecology, and spirituality: The spirit of evolution (2nd ed.). Shambhala.

Although I agree with the view of many contemporary developmental psychologists that infants can sense and perceive differences between internal and external forces (e.g., Rochat, 1995), it is unlikely that their self-other differentiation is precise and fixed. Piaget (1930/1972, Chapter V, Section 3) suggested that infants do not precisely locate the source of internal forces. Indeed, until mental representations of internal forces and the corresponding body are formed, the source of internal forces would not be precisely and stably located in the body. The direct perception of the effects of internal forces (i.e., their outer limits or boundaries; Gibson, 1995; Rochat, 1995), for example, would not enable the identification of their precise source.

Furthermore, Piaget’s (1930/1972, Chapter V, Section 3) account of the role of external resistances to inner tendencies or desires in self-other differentiation is important. When external forces are aligned with internal ones, little difference between them could be perceived. On the other hand, when external forces are not aligned with or oppose internal ones, disjunctions or disconnections between them would be perceived.

“I” is a symbol (signifier) for a concept of the core self (signified). The core self is usually conceptualized as residing in the body (commonly known as the ego), which is corrected through ego-transcendence. Therefore, as a concept of the core self changes, what “I” signifies changes.

The stronger the desire, the more likely it is to be attributed to the ego (though there are exceptions, as in inner conflict). This is why the ego is typically conceptualized as the source of the strongest desires and actions to fulfill them (and thus directly related to the meaning of life).

This worldview likely develops at the Self-Protective stage in ego development: “One kind of transition from the [previous] Impulsive [stage] to the Self-Protective stage is … aware[ness] of frightening impulses in himself and bewildering forces in the world” (Loevinger, 1976, p. 415).

The number of bodies children view as animate decreases as they grow up (Piaget, 1929/1971, Part II). Although this is a developmental step, the essence of animism remains. The fundamental problem of animism is not that purposive forces are not restricted to “animate bodies” but that they are attributed to bodies in the first place. Therefore, it is when the idea of bodies as sources is dissolved that the true nature of purposive forces is understood (see Footnote 6).

This is why even those at the highest stage of ego development, who can balance and unite conflicting perspectives and strive for the ideal of fairness, are still preoccupied with self-fulfillment (Loevinger, 1976). See Cook-Greuter (1999, 2013) and Wilber (2000b, Chapter 8) for the stages of ego-transcendence.

The realization of oneness comes after that of the interdependence or interconnection of all bodies and forces. In the latter, the idea of causal bodies has not been completely dissolved, and thus a belief in self-boundaries remains. When the idea of bodies as sources is completely dissolved, one source and ground of all forces and bodies (i.e., the Self) is revealed. “The great interlocking order was true but partial. … It represented the mutual interpenetration of the Each and the All. But the ground of both the Each and the All was the nondual One” (Wilber, 2000b, Chapter 12, The Great Interlocking Order section).

What is discarded in this transcendence is the ego and exclusive identification with needs and desires you experience, and therefore these needs and desires are preserved and included in the new, wider identity. Wilber (2000a) summarized the transformation of motivation that follows the realization of the Self: “The aim of a complete course of development is to divest the basic structures of any sense of exclusive self, and thus free the basic needs from their contamination by the needs of the separate-self sense. When the basic structures are freed from the immortality projects of the separate self, they are free to return to their natural functional relationships: One eats without making food a religion, one communicates without desire to dominate, one exchanges mutual recognition without angling for self-gain. The separate self, by climbing up and off the ladder of the Great Chain, disappears as an alienated and alienating entity, ends its self-needs altogether, and thus is left with the simple and spontaneous play of the basic needs and their relationships as they easily unfold: When hungry, we eat; when tired, we sleep. The self has been returned to the Self, all self-needs have been met and thus discarded, and the basic needs alone remain, not so much as needs, but as the networks of communions that are Spirit’s relationships with and as this world” (Chapter 9, Footnote 3). One correction I would make is that self-needs (and the striving for self-fulfillment) are discarded not because they have been met but because they have failed to be met satisfactorily.

After self-transcendence, needs and desires are no longer perceived and experienced as an isolated lack but as the same Self or Spirit expressing the entire world. Accordingly, actions now flow from a sense of fullness, which brings forth a fulfilling world without striving for it.

“For many people the only definition of the meaningful life that they can think of is ‘to be lacking something essential and to be striving for it.’ But we know that self-actualizing people [self-transcended people], even though all their basic needs have already been gratified, find life to be even more richly meaningful because they can live, so to speak, in the realm of Being” (Maslow, 1954, Preface XV). Maslow’s discussions about the differences between deficiency motivation and metamotivation and between coping and expression are informative. However, there are several limitations of his theory. For example, it conflates self-transcendence with self-actualization. Moreover, psychological development in general and self-transcendence in particular do not happen by satisfying basic needs, but by trying to satisfy basic needs that are contaminated by exclusive identification and failing (see Footnote 7). I will discuss the developmental process in detail in other posts.